Luchs, Swann and Griffin, (2016) define design thinking as: a systematic and collaborative approach to identifying and creatively solving problems (p. 2). In the same vein, Brown (2008) describes design thinking as “bringing designers’ principles, approaches, methods, and tools to problem solving” (p.1). In describing the nuanced approach within design thinking, Lockwood (2016) asserts that it is: “a human-centred innovation process that emphasises observation, collaboration, fast learning, visualization of ideas, rapid concept prototyping, and concurrent business analysis” (n.p.). This way of thinking was led by Buchanan (1992), who applied design thinking to intractable human problems (e.g. pedagogy of physical literacy), which were not stable but continually evolving and mutating and had many causal levels (Blackman et al, 2006, p.70).

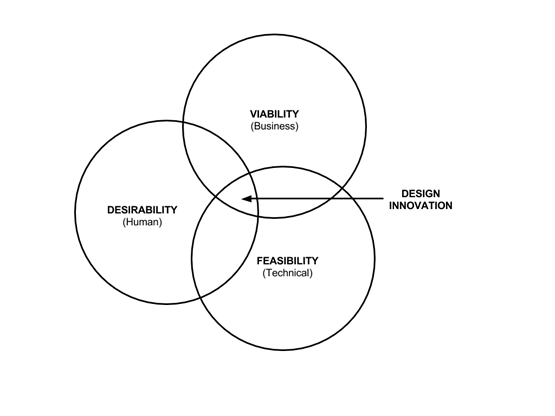

Rittel and Webber (1973) described such problems as ‘wicked’ as they lacked both definitive formulations and solutions and were characterised by conditions of high uncertainty – in Blackman et al’s (2006) words, ‘no single solution applies in all circumstances’ (p.70). Therefore, Buchanan (1992) concluded linear, analytical approaches were unlikely to successfully resolve them. According to Liedtka (2015), problem centeredness, nonlinearity, optionality, and the presence of uncertainty and ambiguity are all defining pillars of design thinking. She believed that such problems benefitted from an experimental approach that explored multiple possible solutions. Wicked problems are so convoluted that their complexity is shared by all stakeholders and thus the end user (e.g. teacher, coach, player, pupil) becomes an active participation. IDEO (2009) presents the ultimate ‘solution’ to a given problem as the sweet spot in Figure 1. The sweet spot is the convergence of what is desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable (Brown, 2016).

Figure 1 : Desirability – Viability – Feasibility Venn diagram (IDEO, 2009)

Figure 1 : Desirability – Viability – Feasibility Venn diagram (IDEO, 2009)